As West and Central Africa progresses through the heart of its rainy season, an unsettling trend is emerging—marked by irregular rainfall distribution, flash floods in the Sahel, and worrying dry spells in typically lush regions. Forecasts for late July through early August 2025 indicate significant rainfall anomalies, with profound implications for agriculture, food security, and livelihoods across the continent.

Diverging Rainfall Patterns: A Tale of Two Regions

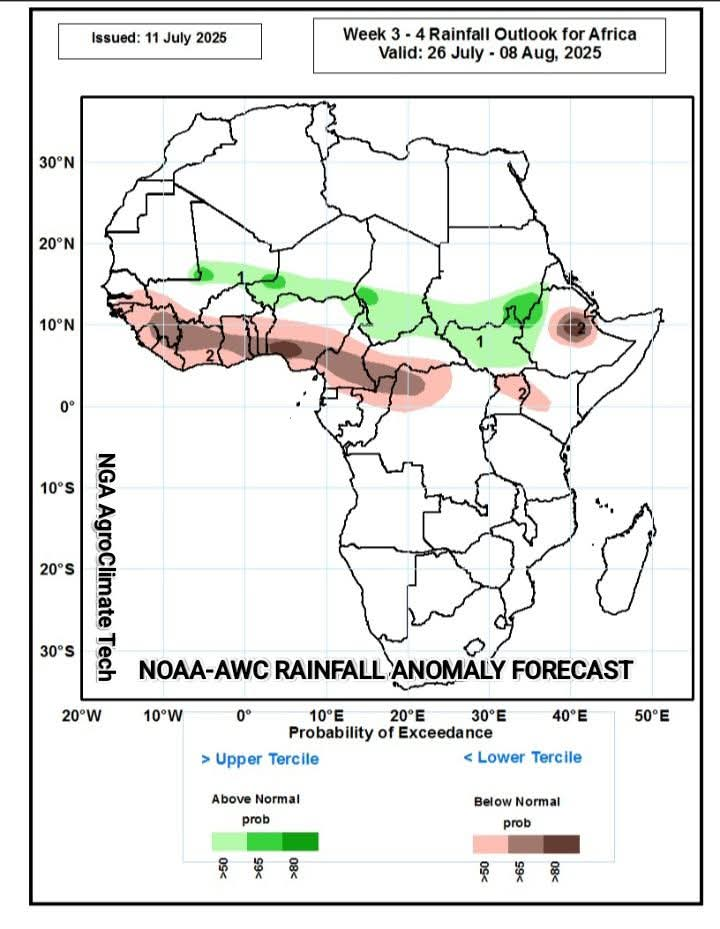

According to regional climate forecasts, including from the African Centre of Meteorological Application for Development (ACMAD), there is a 50–80% probability of below-normal rainfall across a broad swathe of coastal and forested regions, including Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria (severe), Cameroon, Central African Republic, northern DRC, Congo-Brazzaville, Uganda, western Kenya, and much of Ethiopia.

In contrast, the Sahel belt—particularly Mali, Niger, Chad, Sudan, and South Sudan—is expected to receive 50–65% probability of above-normal rainfall, increasing the risk of seasonal floods between late July and early September. These diverging trends mark a troubling deviation from the expected zonal rainfall distribution typically observed during this period of the West African Monsoon.

Drivers Behind the Anomalies: Ocean and Desert Interplay

At the heart of these anomalies are shifts in large-scale climate drivers, particularly sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and land surface dynamics:

1. Colder than Normal SSTs in the Equatorial Atlantic and Gulf of Guinea

Recent satellite observations and oceanic monitoring systems have detected cooler-than-average SSTs in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Guinea. These cooler waters reduce evaporation rates, leading to lower humidity levels in the southwesterly monsoon winds that typically bring moisture inland.

As a result, monsoon rains are weakened or delayed, especially in southern West Africa. Nigeria, for instance, is already reporting extended dry spells in areas like the Middle Belt and southern states, threatening maize, cassava, and yam production, crops that rely heavily on consistent moisture through July and August.

2. Northward Shift of the Intertropical Discontinuity (ITD)

Conversely, the Sahara Desert is experiencing abnormally high land surface temperatures (LSTs), particularly in Mali, Mauritania, and Algeria. This heating drives the ITD, the boundary between moist monsoon air and dry desert air, further north than usual.

This anomalous northward shift, intensified by a steepening pressure gradient between the cool Atlantic and the hot desert interior, is drawing moist air into traditionally arid Sahelian regions, triggering intense downpours and flood risk in urban and low-lying rural areas.

Implications for Agriculture and Food Security

The consequences of these rainfall anomalies are vast and multifaceted:

1. Agricultural Disruption in Coastal and Humid Zones

Regions from Nigeria to Ethiopia are facing crop stress, delayed planting cycles, and increased pest pressure due to prolonged dry conditions. In Nigeria, which accounts for 70% of the region’s cassava and yam production, the Nigeria Meteorological Agency (NiMet) has raised alerts for potential shortfalls in cereal output, which could further inflate prices amid existing food inflation.

2. Rising Flood Risk in Sahelian Nations

In Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan, above-average rainfall could overwhelm urban drainage systems, displace communities, and destroy rainfed crops, especially sorghum and millet. The 2022 and 2023 floods displaced over 2 million people across these regions. With more than 80% of agriculture rain-dependent, these sudden weather swings challenge early warning systems and adaptation capacity.

3. Increased Risk of Crop Failure and Food Price Volatility

The duality of drought and floods means farmers in one part of the region are struggling to get water while others are battling water excess. Such erratic conditions hamper harvest predictability, strain food storage systems, and lead to localized food insecurity, especially in conflict-affected regions of Nigeria, Chad, and CAR.

What Lies Ahead: Outlook for Late August to September

Projections suggest a return of moderate-to-heavy rainfall in late August through September, particularly in coastal West Africa. However, this resurgence may not bring relief but catastrophic floods, as hardened soils from dry spells often fail to absorb sudden downpours, resulting in rapid runoff and flash flooding.

In 2022, for example, over 600 people died and 1.3 million were displaced by floods in Nigeria, with the Benue and Niger river basins most affected. A repeat or intensification of such an event could devastate the already fragile agricultural calendar, further deepen food access gaps, and reverse gains in rural development.

Conclusion: Time for Adaptive Action

This rainfall anomaly underscores the urgent need for climate-resilient agricultural systems, flexible planting calendars, and scalable early warning dissemination across the region.

Governments must:

- Invest in agro-climatic forecasting and downscaled alerts to help farmers plan better;

- Expand irrigation and dry-season farming support, particularly in southern Nigeria and Central Africa;

- Build flood defenses and promote agroecological zoning to minimize displacement and asset loss;

- Boost food reserves and social safety nets to protect the most vulnerable in urban and rural settings.

Climate change is no longer a distant threat, it is altering Africa’s rain cycles in real time. Understanding the mechanics behind these rainfall anomalies can help policymakers, farmers, and humanitarian actors pivot from reactive to proactive, and from crisis to resilience.

~ with insights from NGA AgroClimate Tech